Banks Peninsula Horomaka has around 50 bays, most of which can only be reached by boat. A cursory look at Topo Maps NZ will provide a clue as to why so many. Essentially, when the big volcanoes went off millions of years ago, the lava flows created fingers, with the areas in between eroding away into valleys, bays and beaches.

Several of the larger bays on the northeast side of the Akaroa crater rim – Le Bons, Okains, Little Akaloa, Pigeon, and Port Levy – are accessible by car. They are only about 30 minutes or so from Akaroa, with the notable exception of Port Levy. Each of these bays also has an unusual shape, with long high sheltering ridges on either side of the bays, the remnant lava flows from the ancient volcanoes. The water also displays the most extraordinary turquoise colours, which seems to be a feature of the peninsula’s bays and harbours.

Prior to Europeans arriving, the bays were full of very dense forest and wildlife. The relatively small number of families that settled in the area from the 1840s onwards literally transformed the landscape, converting forests to dairy and sheep farms within a generation. Stop for a moment to take in the rugged peninsula landscape and consider just how tough this was! If you are still not sure, visit the Okains Bay Museum for the personal stories of many of these settlers.

The drive down from Summit Road to the bays is steep and spectacular and the access roads are mostly sealed, albeit narrow in places. Once at water level, there is a mix of beaches, access for boats, and camping in some locations. There is also the occasional walking track if you want to stretch out a bit.

An interesting and largely forgotten factoid – the northeast bays were struck by a tidal wave in 1863 which did some damage. Despite the high surrounding ridges, the valleys leading to the beaches are very flat and low-lying.

Le Bons Bay

The most fun fact about Le Bons Bay is the source of the name. An obvious notion is that it was the name of an early French settler, and that is the completely made up explanation provided by Chat GPT! But there are several other explanations for the name. Pre-settlement whalers called it “the bones bay” due to the large quantity of dry whale bones; or French whalers styled it Le Bon (the Good) Bay; or Captain Le Bas mistook it for Akaroa and sent a boat’s crew ashore – one of the crew was named Le Bon; and so on.

Today, interpreting the name as “good” best describes the reality of the location. It is one of the prettiest beaches on the Canterbury coast with the benefit of safe swimming. At a kilometre wide, there is also plenty of room to spread out. In any event, it is mostly quiet, with a modest number of houses and holiday homes near the beach and no facilities to speak of.

Access to the beach is from car parks behind the low dunes backing the beach, which only take a couple of minutes to cross. If you plan to stay a while you may want to have a beach umbrella or other shelter, as well as food and drinks.

Le Bons Bay is accessible from Summit Road. From State Highway 75, just north of Akaroa, take Long Bay Road to the crater rim then turn left to Summit Road. Le Bons Bay Road is off to the right about 5 kms along Summit Road.

Okains Bay

Okains Bay was purportedly named by a well-known sea trader, Captain Hamilton, who was reading a book written by an Irish naturalist named O’Kain as his vessel passed by. For Māori, Okains Bay is known as Kawatea and it is particularly important to Ngāi Tahu as the first landing place of Ngāi Tahu on Banks Peninsula in the 1300s.

It was first settled by Europeans around 1850. It was heavily forested and a large sawmill was established in 1874, resulting in the mass conversion of the area from forest to farms. A cheese factory opened in 1894 and closed in 1968, which is now the fabulous Okains Museum. Three different wharves have also come and gone, ultimately displaced by better road access.

Today, Okains is arguably the most attractive and accessible of the larger northeast bays for visitors. The view down to the bay from the intersection of Summit and Okains Bay Road is superb, and you can’t beat the fabulous 1 km wide beach, with safe swimming.

From the beach, you can also walk around the southeast side to the first point, with a couple of smaller beaches tucked around the corner. Also on the southeast side, back from the beach by the playground, is a sea cave. On the northwest side, the Opara Stream drains into the bay.

There are some services just before the beach with a cafe and general store, including a petrol pump. Just behind the northwest end of the beach there is a large commercial campground, so the beach is busier than Le Bons to the southeast.

From Akaroa, take SH 75 north to Okains Bay Road. Drive up to the crater rim and across Summit Road down to the bay.

Okains Bay Museum

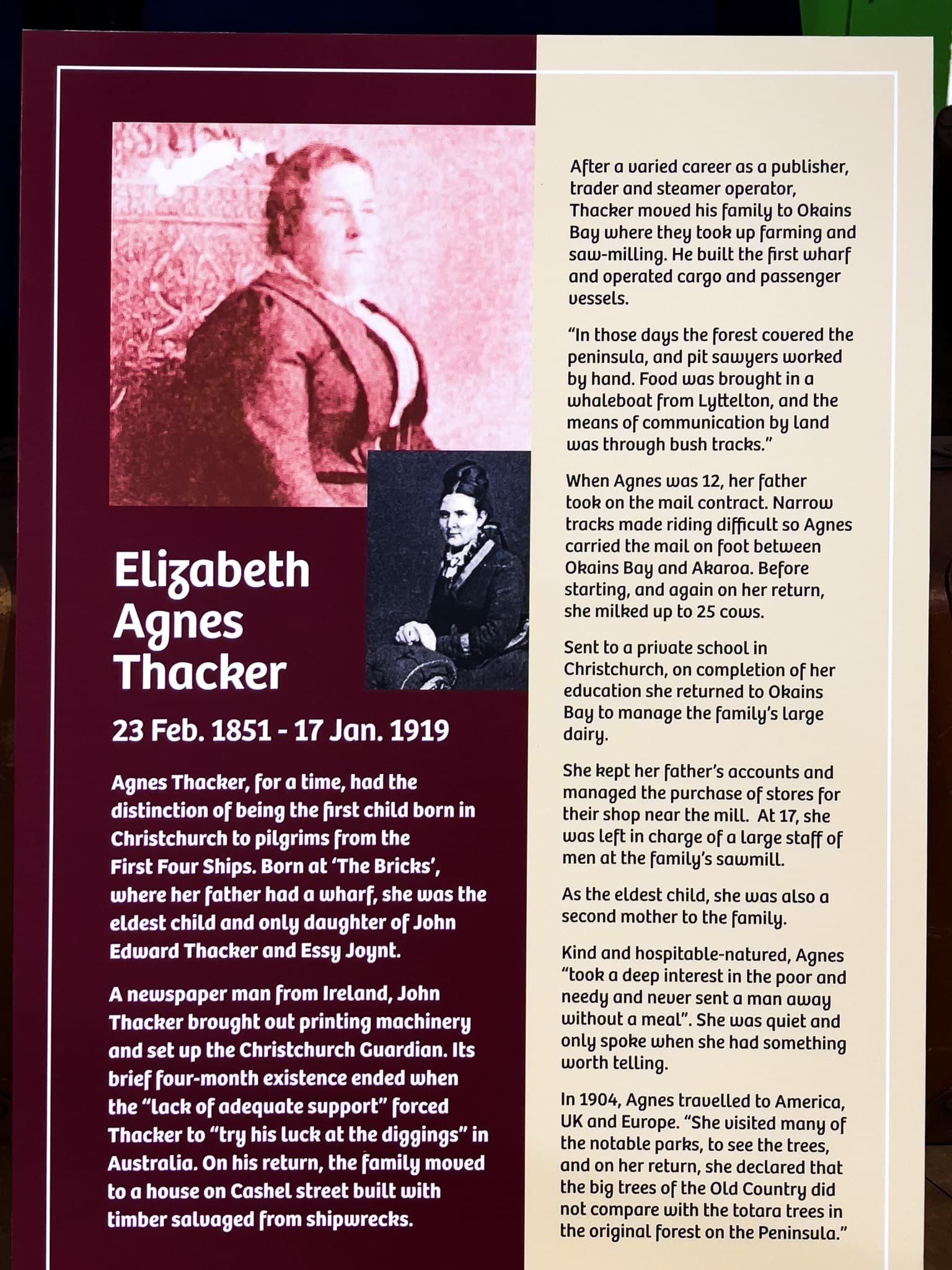

In many ways, the Okains Bay Museum is similar to many small community museums dotted around NZ that tell local stories, typically dating back to the first European settlers and how they lived. But it is more than that, largely thanks to its founder, Murray Thacker.

Murray was a third generation local who grew up in Okains Bay. He developed an avid interest in Māori taonga and as a teenager acquired two collections that had been fossicked from around the region in the 1930s and 1940s. He also fossicked himself before it became illegal.

As an adult, he managed his own farm but continued to develop his private collection at home, including a collection of Māori waka (canoes). In the late 1960s, the closure of the local cheese factory provided the opportunity to establish a proper museum. This took another 9 years and included the relocation and restoration of historic buildings and the construction of the Whakaata, Pātaka and the Whare Taonga by Māori craftsmen. One oddity, which is well to the back of the property, is a turn of the 20th century grandstand!

Today the museum has one of the best collections of Māori taonga and settlement-era artefacts and buildings outside of the major metropolitan museums. It also does a great job of telling the stories of early Māori and Europeans, their experiences, and how they lived day to day.

Little Akaloa Bay

The generally accepted explanation of Little Akaloa Bay’s name is a corruption of Akaroa, this bay being almost due north of Akaroa Harbour. As with the other northeast bays, Europeans arrived around the 1840s/1850s, hacked out the ancient forest and created farms, although the area of flat valley is smaller than at Le Bons. For a while the process was accelerated by the presence of a sawmill.

The beach is quite a lot smaller than those at Le Bons and Okains, only 300 metres wide, and a bit stonier in some places. Swimming is probably best on the east side below the access stairs and rustic changing shed. The small hamlet of houses and holiday homes is also closer to the beach. At the west end, there are several large old trees that provide shelter for a couple of picnic tables.

To get to Little Akaloa, you can either take Chorlton Road from Okains Bay, with views of Stony Bay and Raupo Bay, or from Akaroa, take SH 75 north, turn right into Okains Bay Road then left onto Summit Road on the crater rim. Follow Summit for about 7 kms, then turn right onto Little Akaloa Road. From Little Akaloa, you can also take a winding metal road northwest to the more remote Decanter and Menzies Bays.

Pigeon Bay

Pigeon Bay is a lot longer than most of the bays on Banks Peninsula, about 9 kms from Wakaroa Point to the beach and as such is more like a harbour than a bay. Holmes Bay is a second smaller bay on the west side of the main bay.

Pigeon was named by early whalers for the enormous number of kererū (native wood pigeons) in the forest. The first few European settlers did it particularly tough, arriving in 1844 and carving out a basic existence based on hunting native birds, wild pigs (releases dating back to Cook) and rudimentary cattle farming. In 1850, the first 4 ships arrived in Christchurch, leading to some basic coastal services and a modest expansion of the local community.

As at the other northeast bays on Banks Peninsula, the permanent community did not grow much after this, but it was enough to eliminate the forest and kererū, and to erect a memorial after WWI.

From the hamlet, take Wharf Road north to the campground, a wharf, some boat sheds and a boat park up. Of all the bays, this appears to be the one favoured for boating and you can also easily access kayaks.

There is a walkway at the end of Wharf Road and you can get most of the way down the east side of the bay and climb as high as 320 metres.

Port Levy Pigeon Bay Road

Looking at the map, the quickest way from Pigeon Bay to Port Levy is via the 14.4 km metal Port Levy Pigeon Bay Road. The road climbs steeply up 500 metres and crosses over the ridge below Wild Cattle Hill before dropping back to sea level at Port Levy.

As a rule, we don’t turn down an opportunity to drive a remote NZ road, and this was not an exception. Once again, a Toyota Corolla was tested and came through unscathed.

Having said this, we can’t honestly recommend this narrow, winding unsealed road, with multiple blind corners and no room to get past oncoming vehicles. At least there was no other traffic and the views were fantastic, as you would expect.

The other options for getting to Port Levy are on a sealed road, still offering spectacular views, from Diamond Bay in Lyttelton Harbour or a longer remote drive along Valley Road then metal Western Road from Little River on State Highway 75.

Port Levy

“Port Levy (Potiriwi) / Koukourarata” is one of the weirdest official place names in NZ. Potowiri is presumably a Māori transliteration of the English and Koukourarata is the traditional Māori name of the bay. The European name arose from Solomon Levey, an Australian merchant who sent trading vessels to the peninsula during the 1820s.

Unlike the other northeast bays, there was a Māori community of about 400 people at the time of European settlement, making it the largest Māori settlement on the peninsula. The Ngāi Tūāhuriri (a sub-tribe of Ngāi Tahu) chief Moki named the bay Koukourarata. It was also the home of Tautahi, the chief after whom the swampland Ōtautahi (where Europeans established Christchurch) was named. There are only about 100 full time residents still in and around Port Levy, with the Ngāi Tahu presence denoted by the Koukourarata marae.

The bay itself is sheltered and long, with Port Levy sitting 8 kms from the opening to the Pacific. As with the other bays, European settlement led to farming and intensive clearance of the forests.

Drive north on the east side of the bay to the historic wharf, with car parks and picnic tables. Some time in the 1840s, the first Anglican church in Canterbury was thought to have been built at the end of the reserve and a stone memorial marks the site. The charming current Anglican church was built in 1888.

Port Levy (Potiriwi) / Koukourarata is also a good place to start a hiking trip, with access to a series of connected tracks from Port Levy Purau Road to the southwest or from the end of Richfield Road to the south.

Want more Canterbury Trip Ideas?

Check out our blogs on the Forests and Volcanoes of Banks Peninsula, Touring the Ashburton Lakes to Erewhon, and our Winter Road Trip to Aoraki Mt Cook.